Even as more books are becoming self-published, the world of publishing continues to be a mystery. So for all the would-be authors out there, I'd like to tell you the truth, the naked truth, of one author's story of what to expect when publishing with a traditional publisher. I had a lot of expectations myself once I signed that book contract for the first time, six years ago. And even though I was networking with other mystery writers through Sisters in Crime and learned a lot, there were still some things that I didn’t count on. What can you expect? What will happen next? And what should you be doing in anticipation?

PART ONE:

St. Martin’s, one of the big New York guys, is my publisher. Specifically, the imprint called Minotaur Books. Publishers divide up into imprints that define the sort of books they like to publish. Minotaur Books does mysteries. Since St. Martin’s holds a contest each year that offers a mystery book contract with an advance of $10,000 as the prize, I thought that this was the very minimum I could expect when my agent said that St. Martin’s made an offer. So I rubbed my hands and waited until the news came back to me.

Uh…no. It wasn’t that amount. It was about half of that and just a smidge more. This was disappointing, but as it was pointed out to me, a book has to sell a certain number to make the advance back. And if St. Martin’s is good at anything, it is knowing exactly how many books it could expect to sell in any particular genre. And let’s face it. I was writing an historical mystery, a sub-genre of mystery. And further, I was writing medieval mystery, a sub-sub genre. There were only so many readers out there that I might entice to buy the hardcover. Which became a much smaller number than I would have had to come up with had I gotten a $10,000 advance. It seems small comfort, but you gotta put aside the ego and look at the numbers instead.

So that was fine. After all, I was excited that St. Martin’s, a publisher I had targeted in the first place that I thought could do justice to my series, was going to publish me. I was over the moon.

The contract was for a one book deal. Again, for a newbie in a niche sub-genre, this was probably a decent start. So after my agent hashed out the contract and I signed it, the next thing to happen was my editor going over the manuscript. I don’t know why authors say that editors don’t edit anymore. Sure, they have a slew of other things they have to worry about these days besides editing—marketing and budgets, for instance--and it no doubt cuts into that time, but my editor still edits. He reads it several times and I get back a few pages of notes, observations, and suggestions (this was about five to seven months later. It all depends on when your novel is scheduled for release or how busy your editor is.) Mine is the master of politeness. I don’t know where they go to learn this stuff, but, obviously, he has gleaned how to deal with egos over the years, and he phrases his edits as suggestions and in such a way that I feel that I am doing him the biggest favor ever if I change this or expand on that. I mean, it isn’t as if I have to drive him to the airport. I’m just tweaking a manuscript.

And here’s a tip. I say “yes.” To everything. Well, 99.9% of it. Because he is a professional—been at it over twenty years—and he knows whereof he speaks. Yeah, I know I’m the author, the “Creator”, the “Talent”, but what he’s doing is making smoother prose, making sure the story makes sense, has me expand on details and certain scenes that need more zing or that the reader should spend more time on. I respect that and he in turn respects that I’m a professional and that I should want a better baby. When I say “yes” 99.9% of the time, then that means when there is something worth fighting for—a British spelling on this or that, or opening my chapter the way I originally wanted to—he has no problem saying “yes” back. That’s what we call a professional relationship.

So I made the changes and got the manuscript back to him within the allotted time frame and off it went to the copyeditors. The copyeditors checked my punctuation, grammar, spelling, did fact-checking, and read it again for word sense and sentence structure. In other words, they make sure I don’t look like an idiot. I appreciate the work they do. I hate getting caught actually being an idiot, but what do I know? I just wrote the darned thing, apparently not worrying about such trifles as punctuation and grammar. They send me a manuscript with the changes, asking questions and pointing out boo-boos. (That edit came back to me some three to four months after my editor's edits). Once I made those changes I sent it back with a note of thanks. I’m grateful they caught the stuff that they did.

Then it went on to be “typeset” and designed and put into first pass galleys. It comes to you in loose pages but paginated and in the font in which it will be printed. Basically, it looks just like the book will look. (this arrived a month after I sent back the copy edits). I read the manuscript yet again, and this is the absolute last time--barring any major catastrophes--you get to make changes. Before, with the editor’s notes and even the copyeditor’s notes, you have your chance to make big changes if you want to, adding paragraphs or deleting. But now that it’s been typeset and paginated, big changes will screw up all sorts of things. It’s not unheard of, of course, but it is time-consuming (which means $) and no one likes to do it. You will not be looked upon kindly.

And do read it. This will be the third time since I handed it in to my editor that I will have read my manuscript all the way through. Why? Because with each pass, that’s the only way to catch the clunkers and to make sense of it all. And since this is essentially the last time you will do that before it’s published, you really want to give it a careful once over. Even a twice over if you have the time.

Now it’s down to the wire. With changes made to the galleys, its last trip is to the printers. (At this stage, we were four months from publication date.)

Now, around this time, you’ll get to see the cover. Notice that I didn’t say you’ll get to “approve” the cover. At my level in the midlist, I have no say about my covers. Although, after the very first Crispin book was published with its nice historical novel art, the book was sent to the paperback division. And just so you know how much power they have, they said they wouldn’t print the trade paperback unless we changed the cover art because they hated it.

|

| Original Hardcover |

|

| Re-vamped Paperback |

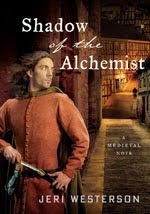

Originally, I was thrilled with the cover art (left) because it was my first published book and it looked okay to me. Not perfect, not something that particularly characterized the “Medieval Noir” concept I came up with, but it was okay. Turned out they ran out of time designing the cover and they had to go with the art that neither my editor nor anyone else seemed happy with. But now, if we wanted a paperback—and we did—the cover would have to be changed. Was there enough in the budget for it? Beats me, because the “budget”—for printing, editing, paying the author advance, marketing--was one of those mysterious things I wasn’t privy to. But apparently, there

was enough for that. And now we were going to do it right. My editor asked me what I thought it should have by way of art (

now they ask me!). I told him that since the series is so character-driven, and it was so unusual to have a medieval PI, that I thought there should be a figure on the cover, maybe a shadowy rendition of the Crispin character with a dark medieval London in the background. He liked that idea, too, and found several cover artists/photographers who specialized in the kind of style we were looking for. Once he nailed down the

photographer, he presented me with a model sheet of the Crispin model they had chosen. Looking at the model, I declared him “drool-worthy.” The model was hired, put in a (correct) costume, and photographed in a billion poses to be used for future covers. The London scenes would be dropped into the background and then the whole would get a digital painterly effect. (see the photo at right)

I love them. They look the way I always pictured they should look. By then, we negotiated a contract for the second book, with, again, a single book contract. This was now 2009, when the financial shit had effectively hit the fan, and sales were down everywhere, including library sales, the bread and butter of my hardcover sales numbers. The publisher was cautious. Understandable. Drove me nuts. Also understandable. But we’ll get back to this in a moment.

Meanwhile, the uncorrected proofs of the book were printed and cobbled together into an Advanced Reader Copy, or arc, and the publisher sent them to newspapers, industry magazines, and other places (like bookstores of record, certain librarians) for reviews, which can be about six months prior to the book’s release. I was also sent the text for the book jacket to approve. At first I thought my editor wrote it, but was happier learning it was done by an intern. I made changes to that and to my bio. I gave them the photo that my photographer husband took of me for my author photo, giving him copyright credit, and it all went into the works.

Prior to my getting a contract, I was fortunate enough to go to my first

Bouchercon, the biggest mystery fan convention on the circuit, and I scored some blurbs from some great authors. I gave St.Martin's those to use in their publicity and in their catalog that goes out the bookstores and libraries. That catalog, by the way, is the main sales tool that publishers use. Not ads, not media blitzing (and certainly not on a little ole midlist author like me), but that catalog. Once it's in a catalog from a big publisher, it is the imprimatur to librarians and bookstore owners that it is worth their notice and their dollars. It helps to have good reviews from the main magazines they use to determine book buying,

BookList and

Library Journal.

They gave me a book release date. And early on I gave my publicist a list of other places, like certain blogs or magazines he may not have thought of (since I was deep into the historical novel community), to send arcs to and to set up a book tour in southern California and Arizona that I could drive to (he booked it, but I would have to get there and pay for it myself. All authors have to pay for their own book tours, unless you are a huge bestselling author, the people who, ironically, can afford to pay for it themselves.) Fortunately, living in southern California affords me many good opportunities for indie mystery bookstore and library appearances. I planned my book launch at a venerable independent bookstore in Pasadena where I used to live, with dueling knights and medieval food, and counted down the days. The pre-order page went up on Amazon and Barnes & Noble. It’s actually going to be a book.

I’ll have to cut it off there. Next month, I’ll continue this story. We’ll talk about bookstore placement and other secrets. Stay tuned.