Friday, July 12, 2013

Reading and Memory

Wednesday, July 10, 2013

Are you ashamed of what you read?

Sometimes I come across articles about writing, reading, and publishing that seem to be referring to an alternate book world that I’ve never experienced. My reaction is: Huh? Where did that idea come from?

Take, for example, a recent article on the Wired magazine website that examined the “surprising” popularity of genre fiction like sci-fi, fantasy, mystery and romance in e-book form. These forms of storytelling, according to the article, “have traditionally lagged behind literary fiction in terms of sales.”

Huh? Where did that idea come from?

A Publishers Weekly/Bowker study a couple years ago showed literary fiction had 20% of the digital market share, outselling any particular genre. But those sales included classics – the e-books that are dirt cheap (and sometimes free) for downloading. How many owners of new Kindles have bought War and Peace or every Jane Austen novel during an initial downloading spree, then never found time to read them as planned?

When it comes to traditional print publishing, can any of us recall a time when genre fiction didn’t dominate bestseller lists? When James Patterson, John Grisham, Nora Roberts and other genre stars didn’t regularly stomp all over literary fiction? The annual Publishers Weekly report on the bestselling books of the previous year confirm that genre rules. The surprising thing isn’t that genre sells well but that there’s any room at all for litfic.

The Wired article names some all-digital genre lines created recently by major publishers – Hydra (SF/fantasy), Alibi (mystery), Flirt (“new adult”), Loveswept (romance) from Random House and Witness (mystery) from Harper Collins – and says the focus on genre fiction “might seem counter-intuitive according to traditional print publishing sales.”

But it’s not at all counter-intuitive. Genre books, particularly romance and crime fiction in all their many varieties, are big sellers in print, so it makes sense to assume they’ll sell well as e-books. And they do. Some genre books sell more digital copies than print.

Why? Some sensible reasons are advanced in the article, but the first one mentioned is this: If it’s an e-book, you won’t be embarrassed by other people being able to see what you’re reading. That sounds an awful lot like: Nobody can see you’re reading trash.

Antonia Storer, a columnist for The Guardian, is quoted as saying she’s more comfortable reading “downmarket” fiction in secrecy on an e-reader and “keeping shelf space for books that proclaim my cleverness.” In a column last year Storer wrote, “The reading public in private is lazy and smutty. E-readers hide the material.” After you stop rolling your eyes, go read the rest of the column. It’s quite entertaining.

|

| Put a cover on your e-reader to make sure nobody can see what kind of trash you're reading! |

Digital-first publishing allows publishers to take more chances on new authors and work that might not make a profit in print. Novellas, for example, have more chance of being published profitably (or published at all) as e-books. As Stehlik says, e-books have liberated publishers from the profit/loss limits of print – and they have freed writers and readers as well.

But it appears we still have a long way to go to free ourselves of prejudice against genre fiction. I’m not ashamed of what I read. I’m not ashamed of what I write. If you see me reading on my tablet, it’s not because I’m hiding something. It just happens to be a convenient way to carry around a ton of books so I always something to choose from.

Wednesday, November 9, 2011

Why do we need stories?

The next time you’re in the fiction section of a library or bookstore, take a minute to really see what’s around you. Each of those novels holds between its covers a distinct world that was created inside someone’s head.

Every year thousands of fictional worlds, inhabited by nonexistent people living out imaginary lives, are written, published, and sold. The human hunger for made-up stories is insatiable – and unique. No other animal feels a desire, a need, to live simultaneously in the real world and in a wild variety of alternate, imaginary worlds.

Why do people have such a strong compulsion to tell and to hear, to write and to read, fictional versions of human experience? Why isn’t reality enough?

Reading fiction is usually seen as an escape from reality – so much so that many parents worry about children who “read too much” and don’t spend enough time interacting with other kids. They fear that their children will be isolated and fail to develop the “people skills” necessary to succeed in society. A series of psychological studies done over the past few years, though, should set the parents’ minds at ease. In every study, frequent readers of fiction were shown to be more understanding of other people’s viewpoints, better at reading the moods of others, and more open to new experiences. They suffered less from loneliness and social isolation than people who read primarily nonfiction.

Fiction has social benefits even when it’s not in print form and bound between covers. In a 2010 study of pre-school children, a team of psychologists found that the more fictional stories the kids listened to, and the more fictional movies they saw, the better able they were to understand other people’s viewpoints and beliefs. Watching television, however, didn’t provide the same benefits. The psychologists theorize that TV shows are too simplistic and don’t challenge the mind and emotions the way more complex forms of fiction do.

We need stories in order to make sense of human life. While we’re immersed in a fictional world, we set aside our own beliefs and concerns and adopt the point of view of the protagonist. The two worst things we can say about any fictional person are “She/He didn’t seem real to me” and “I didn’t care about the character.” Most of us don’t read fiction out of mere curiosity, to watch characters we don’t care about move through a series of events we can never accept as real. We want to be pulled into the story. We want to lose ourselves in the fictional world. We want to understand it, however different it may be from our own experience. Understanding fictional events and people makes us more open-minded in the real world.

If you’d like to read details of studies done in this area, look for an article by cognitive psychologist Keith Oatley in the November/December issue of Scientific American Mind. (You will not be able to read the entire article on the magazine’s website.)

If you’d like to test whether your immersion in fiction has sharpened your ability to read other people’s emotions, take this free online test:

If you’d like to test whether your immersion in fiction has sharpened your ability to read other people’s emotions, take this free online test: http://glennrowe.net/BaronCohen/Faces/EyesTest.aspx

Come back afterward and tell me how you scored!

********************

Speaking of stories and books, December 3 is the second annual Take Your Child to a Bookstore Day. Click on the link to read about it, then spread the word!

Wednesday, May 25, 2011

The Good Reader

Somebody on DorothyL asked a few days ago, “What makes a good reader?” As in, we know what readers expect from writers (perfection!), but what do we expect – or at least wish for – from readers?

I’ve been extraordinarily lucky in my contacts with readers. I love hearing from them. I’ve received many e-mails and in-person comments that were so wonderful and gratifying that they kept me going for weeks afterward. I’ve suffered only indirect blows from those who think the very existence of my books is an affront to everything they hold dear. My portrait of The Good Reader is drawn from the experiences of other writers as well as my own.

The Good Reader pays attention to what she’s reading and does not complain to the writer about nonexistent errors or omissions.

The Good Reader lets an author know that she has read and enjoyed the writer’s book(s).

The Good Reader doesn’t rush to ruin an author’s day/week/year with a long e-mail or online “review” detailing every reason large and small why she hated the writer’s new book.

The Good Reader realizes that few authors make much money, that most of us do this because we love to write, that a single book represents a year or more of intense creative work, and it’s disheartening, to say the least, when a reader makes it her personal mission to go around the internet urging everybody, everywhere, to shun it. The Good Reader realizes that his or her taste may not be shared by all readers.

While The Good Reader is certainly entitled to express an opinion, she doesn’t use online reviews to instruct a professional author on how to improve his or her writing in future books. That’s an editor’s job.

(Note: Many professional writers make it a point to avoid looking at reader reviews on sites like Amazon.)

The Good Reader realizes that the characters in a book are not stand-ins for the author who created them. If a character does something awful or expresses an unfortunate opinion, that doesn’t mean the writer behaves or thinks that way.

The Good Reader may voice a wish for the future direction of a series character’s life – as in, “I’d love to see her marry Tom” – but doesn’t become aggressive about it (as in, “If they don’t get married soon, I’m going to stop reading your books”).

The Good Reader realizes that an author with a traditional print publisher probably has no control over the release of an e-book version of her novel. The Good Reader doesn’t ask about the e-book repeatedly, then when it’s available, decide not to buy it after all.

The Good Reader doesn’t ask an author published by a small press why her books aren’t all prominently displayed at the local Barnes & Noble.

The Good Reader doesn’t tell an author that she looks nothing like her picture on the book jacket.

I’m sure any writer who’s reading this could add to the list. Feel free.

Wednesday, September 22, 2010

I wish I'd been warned...

Do you ever wish novels came with warning labels?

Something like: WARNING! This book could plant images in your mind that will disgust you and haunt you forever.

As a writer, I hate the very idea. I don’t want anyone passing up a book because of a label that might not apply to everyone. As a reader, I’ve sometimes wish I’d had a little warning about the content of a novel.

Ironically, this happens most often when I’m reading a book by a favorite author, and it’s usually my own fault. If I love an author’s work, I avoid most reviews of a new book so the story won’t be spoiled for me, but that also means I’m not prepared if it contains horrific scenes that I’ll find revolting. I’m talking about scenes in which the torture of women is described graphically and at length. I’m talking about similar scenes involving animals. And scenes in which children are abused or molested in any way.

Ironically, this happens most often when I’m reading a book by a favorite author, and it’s usually my own fault. If I love an author’s work, I avoid most reviews of a new book so the story won’t be spoiled for me, but that also means I’m not prepared if it contains horrific scenes that I’ll find revolting. I’m talking about scenes in which the torture of women is described graphically and at length. I’m talking about similar scenes involving animals. And scenes in which children are abused or molested in any way.Like all mystery readers, I have no problem with ordinary murder. People are murdered all the time. It’s part of the world we live in, and as a storytelling device that allows for the exploration of human motives and society, it is unsurpassed. As a writer, I try to make murder scenes realistic, and that may involve unpleasant details about the state of the body. I can usually read such things, and write them, then put them out of my mind.

Some images, though, won’t go away, and I’d rather not put them into my head in the first place. I avoided reading one Minette Walters novel – although I admire Walters enormously – because I was told it contained descriptions of animal abuse. When I came upon a scene about a cat being tortured in a Robert Crais novel, I had to skip it. The whole point of the scene was to show that Joe Pike had a compassionate heart underneath his silent, forbidding exterior, and I had already seen that demonstrated many times in previous Crais novels.

My most recent “I wish I hadn’t read that” experience was with Nevada Barr’s new book, Burn. (If you plan to read it and don’t appreciate spoilers, you may depart now.) I looked at one review in advance, but it didn’t raise any red flags for me. I listened to the unabridged audio of the book, and although the characters didn’t appeal to me I love Barr’s work and her protagonist, Anna Pigeon, and I never thought of abandoning the book.

I listened to most of Burn with no particular reaction one way or the other. I could tell it would turn out to be about the sexual enslavement of children, and I applauded Barr for tackling such an important and disturbing topic. Then, toward the end, I suddenly found myself listening to graphic descriptions of small children performing sex acts on men in a popular New Orleans establishment and being physically abused in other ways. I continued listening, or half-listening, thinking this part of the book was necessary to make the author’s point and would pass quickly. It continued for many pages, though, and I have only myself to blame for not quitting when I should have. Now the images vividly created by a gifted author are in my memory to stay, and I wish I had passed on that installment of the series.

After finishing the book, I read the reader reviews of Burn on Amazon and was shocked by the virulent tone of many of them. A lot of people seemed personally offended that Barr chose to write about children being used for sex by men. One person called the book “prurient” and implied that Barr was peddling pornography. As a writer, I have to be on Barr’s side (not that she will ever know or care about my opinion). I am opposed to official censorship. I hate the idea of any author being told what he or she may write about. Our constitution guarantees freedom of speech, and that’s a freedom we should all protect vigilantly – even when we don’t happen to like what’s being said or written.

As a reader, though, I have another right: to choose what I read and to pass up what doesn’t appeal to me. Maybe I’m a weakling, or oversensitive, but there are some things I don’t want to read about and plant in my mind forevermore. I don’t believe in censoring writers, but as a reader I practice a kind of self-censorship. And after my experience with Burn, I’ve decided that in the future I will have to read more reviews, and read them more carefully, before I read the actual books.

What about you? Are there certain topics that will always make you pass up a book? Do you ever wish you had clearer warnings about disturbing content in novels?

Wednesday, February 17, 2010

The Everyday Miracle of Language

If you’re reading a writer’s blog, reading is probably an important part of your life. Maybe you’re like me – you’re compelled to fill idle moments with words, and your eyes seek out print wherever you are. If you forget to take a book to the doctor’s office, you’ll read six-month-old issues of People and Sports Illustrated in the waiting room. Anything will do, as long as you can read.

Writing and reading are uniquely human activities, unlike language itself. Most animals have some sort of language, a way of communicating with others of their species. Dogs bark, cats meow, monkeys screech to alert others to danger, birds sing or call to attract mates, claim territory, sound alarms. Honey bees “talk” to each other with dance-like movements that identify the locations of good foraging spots. One way or another, animals communicate with other animals.

Humans, however, are the only animals that can write and read our languages. How did our species develop the ability to preserve and pass on information by using marks on a page? What goes on inside our brains when we read those little marks? And what do tree branches have to do with reading?

Humans, however, are the only animals that can write and read our languages. How did our species develop the ability to preserve and pass on information by using marks on a page? What goes on inside our brains when we read those little marks? And what do tree branches have to do with reading?You won’t be surprised to learn that this subject has been studied in depth – we’re also the only animals who examine their own behavior to find out what makes themselves tick.

French cognitive psychologist Stanislas Dahaene, author of Reading in the Brain, is one of the most prominent researchers into the neuroscience of reading. He talks about his discoveries and observations in an interview in the March/April issue of Scientific American Mind. When we read, regardless of the language, we all use a region of the brain in the left hemisphere that Dahaene has nicknamed “the letterbox” – the visual word-form area. The “letterbox” is part of a larger brain area that helps us recognize objects, faces, and scenes and is especially attuned to natural shapes in the world around us. When humans began writing their languages, they created symbols – letters – using shapes the brain already knew.

Every written language on earth uses the same basic shapes drawn from nature. For example, if you look up at a tree, you’ll see the “Y” shape over and over. Keep looking and you’ll see all the angles, curves, and circles that people have woven into their written languages.

The marks we call letters have no inherent meaning, either alone or combined with other marks to form what we call words. They mean whatever we say they do. When children learn to read, they’re actually learning to decipher a form of code – grasping the idea that each “word” represents an object or an abstract concept – and learning to do it so rapidly that it becomes automatic. That’s a monumental achievement for a little kid, don’t you think? And yet the vast majority of children are able to do it early in life.

The next time you see a kid reading something, whether it’s a novel or a comic book or a web page, take a minute to appreciate this everyday miracle and to remember, if you can, the excitement you felt when learning to read opened up the whole world of written language for you.

Wednesday, December 30, 2009

A Year of Books

I’m always disheartened when I look over my list of books I’ve read – or listened to – during the past year and realize I can’t recall a thing about many of them. No, this isn’t a consequence of advancing age. It’s always been the case: a lot of the books I read are instantly forgettable.

If I can remember the plot or style or – most important – the characters in a novel months after reading it, I know there’s something special about that book. It’s either very good or unforgettably bad. This year my list has an unusual number of terrific novels on it (some of them published in previous years).

My favorite was The Help by Kathryn Stockett, not a mystery but a surprisingly suspenseful story about a young white woman in the 1960s south who secretly transcribes and publishes the tales told by black maids working in white households. This was a time and place when white people could kill blacks with impunity, so the risks taken by “the help” in the novel are enormous. The story is spellbinding and every character is unforgettable.

My favorite was The Help by Kathryn Stockett, not a mystery but a surprisingly suspenseful story about a young white woman in the 1960s south who secretly transcribes and publishes the tales told by black maids working in white households. This was a time and place when white people could kill blacks with impunity, so the risks taken by “the help” in the novel are enormous. The story is spellbinding and every character is unforgettable.I also loved The Last Child by John Hart, another intense, gripping novel set in the south. The child of the title is a boy who has watched his mother slowly destroy herself with drinking and an abusive relationship since her daughter disappeared. The young son is determined to find his sister, dead or alive, and give his mother some degree of peace. His probing sets off a string of terrifying consequences. I found The Last Child riveting, and I think it’s the best Hart has published so far.

I read two Michael Robotham novels this year, Shatter and The Night Ferry, and this writer is now on my must-read list for his future work. Shatter is about a man whose past comes back to haunt him... only trouble is, he doesn’t believe it is his past. The Night Ferry is equally gripping but utterly different, except for the always superb writing. It introduces Alicia Barba, a British police detective who is the child of Indian immigrants, a character I would love to see in a series. When an old friend is murdered, a shocking revelation sends Alicia on a hunt for the truth about her friend’s life and the baby everyone thought she was about to have.

I read two Michael Robotham novels this year, Shatter and The Night Ferry, and this writer is now on my must-read list for his future work. Shatter is about a man whose past comes back to haunt him... only trouble is, he doesn’t believe it is his past. The Night Ferry is equally gripping but utterly different, except for the always superb writing. It introduces Alicia Barba, a British police detective who is the child of Indian immigrants, a character I would love to see in a series. When an old friend is murdered, a shocking revelation sends Alicia on a hunt for the truth about her friend’s life and the baby everyone thought she was about to have. Gillian Flynn’s Sharp Objects is a stunning debut. Her lead character is a young female newspaper reporter with a history of emotional problems that included a compulsion to cut herself. Now she’s out of treatment and must return home – the source of her troubles – to write about the murders of several children. Flynn’s insight into human behavior is keen and her prose is as sharp as the razors that tempt her heroine. The conclusion of the book is going to stay with me for a long time.

Gillian Flynn’s Sharp Objects is a stunning debut. Her lead character is a young female newspaper reporter with a history of emotional problems that included a compulsion to cut herself. Now she’s out of treatment and must return home – the source of her troubles – to write about the murders of several children. Flynn’s insight into human behavior is keen and her prose is as sharp as the razors that tempt her heroine. The conclusion of the book is going to stay with me for a long time.The Brutal Telling may win Louise Penny a third Agatha Award and a few other honors as well. She’s on a par with Julia Spencer-Fleming and Nancy Pickard, producing traditional mysteries with all the expected features – the familiar community, the beloved regular characters, respect for the gravity of murder without dwelling on the gore – plus the emotional depth and insight found in the best literature.

When Will There Be Good News? is, in my opinion, the best of Kate Atkinson’s Jackson Brody novels. Her books are considered more literary fiction than crime novels, but this one is as compelling as any mystery or thriller I’ve ever read. The opening sequence left me gasping in shock.

I loved Karin Slaughter’s Undone because it brought together Dr. Sara Linton from her Grant County series and Will Trent, the GBI agent from Fractured. This is a powerful story, perhaps the best Slaughter has ever written.

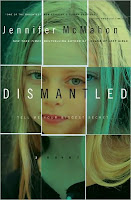

Other novels I enjoyed this year are The Wrong Mother by Sophie Hannah, Dismantled by Jennifer McMahon, Death and the Lit Chick by G.M. Malliet, Exit Music by Ian Rankin (the last Rebus novel), The Blood Detective by Dan Waddell, The Private Patient by P.D. James (possibly the last Dalgliesh novel), The Keepsake by Tess Gerritsen, Careless in Red by Elizabeth George, Sand Sharks by Margaret Maron. I've just started Jeri Westerson's Serpent in the Thorns and I can tell already it's going to be one of my favorites. I have lots more 2009 releases that I haven't gotten to yet.

Other novels I enjoyed this year are The Wrong Mother by Sophie Hannah, Dismantled by Jennifer McMahon, Death and the Lit Chick by G.M. Malliet, Exit Music by Ian Rankin (the last Rebus novel), The Blood Detective by Dan Waddell, The Private Patient by P.D. James (possibly the last Dalgliesh novel), The Keepsake by Tess Gerritsen, Careless in Red by Elizabeth George, Sand Sharks by Margaret Maron. I've just started Jeri Westerson's Serpent in the Thorns and I can tell already it's going to be one of my favorites. I have lots more 2009 releases that I haven't gotten to yet.I feel as if I’ll never catch up with all the books I want to read, and now here comes 2010 with a whole new crop. Erin Hart’s False Mermaid in March, Julia Spencer-Fleming’s One Was a Soldier and Elizabeth George’s This Body of Death in April... Do you ever wish you could drop everything and just read for a few months?

What books did you love in 2009? What are you looking forward to in 2010?

Thursday, December 4, 2008

Reading and the Holidays

Holiday shopping season is upon us, and not only do books make wonderful presents (to give and to receive), but books also played a part in shaping my perceptions and expectations of the holidays. I suspect that this is true for many people.

A couple of weeks ago, I mentioned the great opening line of Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women: “ ‘Christmas won’t be Christmas without any presents.’” Yes, all the way back in 1870, there was no surer way to disappoint a child than not to provide Christmas presents. Thanks to Alcott’s high moral Transcendentalist principles, what the March girls actually do is quit complaining, decide to put their annual one-dollar spending money into presents for their mother instead of treats for themselves, and end up giving away their festive holiday breakfast to an impoverished immigrant family with too many children. Generations of American girls have internalized the lessons in that story.

I can’t remember the name of the 1950s children’s book in which the family had a tradition of reading Dickens’s A Christmas Carol aloud on Christmas Eve, but the idea of such a tradition has stuck with me all these years. I also remember that the youngest boy was in the choir, and there was great tension about whether he would be able to hit the high note in his solo, “Glory to God in the highest,” presumably from Handel’s Messiah. (He did.) I shouldn’t have been paying attention to Christmas at all as a kid, but my Jewish parents were so afraid we’d feel deprived if we couldn’t participate in the general fuss that we decorated what we facetiously called a “Chanukah bush” and got stockings stuffed with presents on Christmas morning. Today, I’m sure there’s an abundance of books about Jewish families celebrating Chanukah and other holidays, but I don’t remember any back then.

In my ecumenical present-day family, we celebrate both holidays. I must admit that rather than reading aloud, we watch movies made from the great books already mentioned: Alastair Sims as Scrooge in A Christmas Carol and the Gillian Armstrong version of Little Women, which my husband and I both like in spite of the the terrible miscasting of Winona Ryder as Jo. I recently learned that an old friend from college and her family read Dylan Thomas’s A Child’s Christmas in Wales aloud every year. So I know that the tradition of holiday reading does survive.

No gift list in our family is complete unless it includes at least one book. Bookstore gift certificates are also a guaranteed successful present, but I, for one, am not happy unless there’s at least one fat hardcover by a favorite mystery author that I wouldn’t have bought for myself under the tree, so I can curl up on the couch with it at some time during the long, lazy day. Books are the present of choice for my stepdaughter and her husband, who live in London, because we can order just what they want from their amazon.co.uk wish lists and have them shipped free. Talk about books I’d never order for myself! And one of the great shopping pleasures these days is buying books for my granddaughters. In the 21st century, there are children’s books about everything. On my last visit the almost-two-year-old had me read her one entitled It’s Potty Time, with separate illustrated editions for boys and girls, and it’s only one of dozens on the subject.

What books are on your holiday gift list? What books, if any, shaped your image of how holidays should be?

Wednesday, January 30, 2008

Love it? Don't read it again

One thing I’ve learned from moderating a mystery book discussion group for writers is that few crime novels stand up to close inspection or even a second reading for pleasure. More than once I’ve recommended a book to the group because I loved it and thought we could learn from it, only to discover during our detailed (and merciless) discussions that I don’t admire it that much after all.

You might think this happens because a mystery or suspense novel – any novel, actually – is an artificial construct, with the clear beginning, middle, and neat ending we seldom see in real life. The more closely we look at a novel, the more unreal it seems. That certainly has an effect, but it’s not the only reason why books we love can disappoint us on a second reading.

One explanation is that people change but books don’t. If you read a novel for the second time a month after the first, you will be a marginally different person and might see some flaws you missed initially. Wait five years and your interests and emotional life might be so different that you wonder how anything in that book could have pleased or moved you.

The books we never grow tired of, the ones we label “classics” – Jane Austin’s novels, for example, or the works of Mark Twain and Charles Dickens – stand up to repeated readings or viewings as movies or TV dramatizations because they tell universal stories that touch us regardless of where we are in our own lives.

To Kill a Mockingbird is widely regarded as the greatest American novel ever written, and it continues

to sell many thousands of

to sell many thousands ofcopies every year. I have read it more than once and seen the movie more than once, and I doubt I’ll ever tire of it. But each time, I’ve seen it in a different light because I’m a different person. Sometimes I’ve identified with Scout, at other times with Atticus, and for a while, Boo Radley was the character I felt I had the most in common with. Mockingbird is a perfect novel – beautifully written, cleanly structured, with characters and a message that transcend time and place. The story makes sense, however many times you read it.

Few books have all of those virtues, and the mystery genre, like romance, is the home of many novels that are intended to entertain and quickly be forgotten. If you read them a second time, your emotions won’t be fully engaged again, and your mind will rebel against any clunky writing, questionable plot turns, shallow characters, and weak motivations you overlooked (or noticed but forgave) the first time around. Just as few novels have all the virtues, few have all the flaws, but most books have some of them.

In discussing crime novels, a major problem my group often sees is weak motivation. I’ve been surprised more than once, when re-reading a novel I enjoyed the first time, to discover the characters have little reason to behave the way they do. This flaw comes hand in hand with weak characterization. The character might be vividly depicted, we might be able to “see” him or her clearly, but if we don’t understand the person’s inner life, we can’t understand why an apparently sensible human being is doing dangerous or hurtful things. Without that understanding, the plot won’t make sense. Why didn’t I see the flaw on the first reading? Maybe I liked the writing style or the atmosphere or the suspense and let those elements blind me to the problems.

Some books, though, not only stand up to more than one reading but provide me with fresh insights each time. I’ve admired Thomas H. Cook’s Mortal Memory and Breakheart Hill more with each reading. Laura Lippman’s Every Secret Thing did not disappoint me the second time around (and it was a great book for discussion and dissection). I have a feeling that Laura's What the Dead Know will seem just as wonderful if I read it again. I’ve studied some of Tess Gerritsen’s and Lisa Gardner’s books in great detail in the hope of absorbing their suspense techniques. I’ve read parts of Dennis Lehane’s Mystic River over and over. Reading crime fiction is probably the best way to learn how to write it, but you have to choose your study material carefully.

Some books, though, not only stand up to more than one reading but provide me with fresh insights each time. I’ve admired Thomas H. Cook’s Mortal Memory and Breakheart Hill more with each reading. Laura Lippman’s Every Secret Thing did not disappoint me the second time around (and it was a great book for discussion and dissection). I have a feeling that Laura's What the Dead Know will seem just as wonderful if I read it again. I’ve studied some of Tess Gerritsen’s and Lisa Gardner’s books in great detail in the hope of absorbing their suspense techniques. I’ve read parts of Dennis Lehane’s Mystic River over and over. Reading crime fiction is probably the best way to learn how to write it, but you have to choose your study material carefully.As for my own published books, in the course of rewriting, editing, and proofing, I've read both of them so many times that I'm thoroughly sick of them. I know what their flaws are. But if you read them only once, maybe you'll overlook the flaws -- or at least not mind them too much.

Have you ever read a book a second time and wondered why you liked it the first time? What is most likely to disappoint you if you look too closely – plot, character, writing style?

Saturday, January 5, 2008

Read All About It

by Darlene Ryan

When I was growing up we took the bus into the city every second Saturday to go to the library. The library was a beautiful old stone building with an imposing set of stairs up to the front doors, high ceilings and shelves of books that reached way over my head. It was funded, in part, by philanthropist Andrew Carnegie. (Why he helped pay for a library in a small Canadian city I don't know.) Every visit I’d take home a stack of books that had to last for two weeks and somehow never did.

Now I’m taking the munchkin to the library--and still coming home with a stack of books for myself. She’s too old now for Robert Munsch, but I still sneak out with Love You Forever or The Paperbag Princess once in a while. A couple of weeks ago she came home from the school library with There’s An Alligator Under My Bed, not for herself—it’s another book she says she’s to o old for now—she brought it for me, because it was always one of my favorites. At least that’s what she said.

o old for now—she brought it for me, because it was always one of my favorites. At least that’s what she said.

I can’t imagine life without books. With books I’ve gone places I’ll never visit and done things I’ll never get to do. There’s almost no chance I’ll ever end up at the

In honour of Family Literacy Day, on January 27, here are some ideas to get everyone reading a little more.

Take the kids to the bookstore. Buy everyone a book, bring the books home and read them together. (Some not-so-enthusiastic readers can be enticed with a graphic novel.) If they aren’t your children, check with their parents to see if anything is off limits. Too scary, for instance.

When you’re out with kids read the street and store signs with them. If you’re looking for an address have a child watch for the street name and building number. Hey, let’s face it. Their eyes are sharper than ours.

Ask a child to read the recipe to you when you cook. This is actually very helpful if like me you need glasses to see the recipe, but find they tend to fall into the bowl when you’re mixing.

Stick a chalkboard or a white board in the kitchen and write notes to each other. When the munchkin was learning to read I’d spell out a couple of supper choices on the refrigerator with magnetic letters and she got to choose what we’d have—Rice or Potatoes, Corn or Beans, Fruit or Cookie. No surprise, cookie was the first word she figured out.

Read the newspaper together. Look for mentions of your child’s school on the sports pages. Follow their favorite baseball team or hockey player. Take turns reading the comic strips to each other.

Visit the library. And don’t limit yourself to the children’s department. Borrow a cookbook. Learn how to make authentic curry or sushi—at least on paper. Take home back issues of National Geographic—or Rolling Stone.

And check out up-coming activities. Thanks to the library we’ve made our own pretzels and ice cream, we’ve learned to weave and make paper maché, we’ve created some spectacular paper airplanes and exploded a volcano in the middle of the kitchen. And we’ve learned it’s better to explode a volcano outside.

Write to the children in your life. Exchange email or snail mail. The munchkin, for instance, loves “real” mail. Share funny stories from your own childhood or about their parents. Ask questions that can’t be answered with a yes or no.

Encourage kids to make up stories and poems and write them down. One night a week at dinner share them. Parents too. Give dollar store prizes for the funniest poem or the scariest story. Invite friends to join you with their stories.

Let your kids see you read. Adults who read are more likely to have kids who read. (At least in my experience.)

Saturday, August 25, 2007

Guest Blogger Don Bruns

One in four adults read no books last year. It's a lead story in newspapers today. According to an Associated Press-Ipsos poll released Tuesday, of those who did read, women and seniors were most avid and religious works and pop fiction were the top choices. The typical person read four books in the last year. Half read more and half read fewer. Excluding those who hadn't read any, the usual number read was seven.

Analyists attribute the listlessness to competition from the Internet and other media, the unsteady economy, and a well-established industry with limited opportunities for expansion.

If pasta dishes were overtaking beef dishes in popularity, the Beef Industry would band together and have a national campaign, and maybe do commecials that said something like "BEEF, IT'S WHAT'S FOR DINNER!"

Or if the milk industry was experiencing flat sales, the Dairy Industry would probably come up with a campaign that said "GOT MILK?"

Instead, the publishing industry keeps pushing top tiered authors, and their own books to try and capture the seven books per reader.

There's nothing wrong with that, but I wonder why the major publishers can't band together for a campaign that doesn't sell individual books. A campaign that promotes the excitement of reading. A series of billboards, television ads, print pieces, that show someone reading...on a beach...in bed...in an easy chair, on the train, on a plane, in a restaurant, in a library...and the catch phrase could be "A good book can go anywhere!" Or pictures of exotic locations, with the slogan "A book can take you anywhere." Or just a series of print ads that say..."Caught you reading. Read a good book lately?" Or maybe a campaign that shows a parent reading, and a little kid next to the parent with a book. The slogan could be "Kids learn good habits by example. Read a book!"

It seems to me that the publishing industry could help put some excitement back into reading. And if we could just get each reader in America to read one more book a year...just one, it might be mine. Or yours.

Don Bruns is a mystery writer with a new release Sept. 2007.

Stuff To Die For is not only a book, but a short movie. You can learn more about both at www.donbrunsbooks.com

Thursday, May 31, 2007

Remembering Books

One of the reasons I love being part of the mystery community is the sense of belonging that I get as a reader. It’s not just about mysteries. As a member of DorothyL, an e-list that’s nicely balanced among mystery-loving readers, writers, librarians, and booksellers et al., I marvel at how often these kindred spirits love the same books, all kinds of books, that I do. Even the vigilant moderators have been known to relax the mystery-only rule if the book or author is universally beloved, like Lois McMaster Bujold, whose A Civil Campaign (a perfect cross between comedy of manners and galactic space opera) just might be my favorite book. I remember one extended discussion on DorothyL in which quite a number of DLers admitted they’d go to bed with Bujold’s protagonist Miles Vorkosigan, a brilliant and charismatic charmer who was born with brittle bones and is very, very short.

The kindred spirit phenomenon is most evident among the bookish when the conversation turns to childhood reading. It was on DorothyL once again that I discovered I wasn’t the only kid who loved a book called The Lion’s Paw. It was about some orphaned kids who sailed to the then remote Sanibel Island in the Florida Keys to find a rare shell that would make their fortunes. It’s not in print, but you can buy it through Amazon, which reminded me of the author’s name (Robb White) and displayed a review by a reader who said, “Now that I can collect the books I loved as a child, I look forward to obtaining a copy to read again!” Yep—kindred spirit.

As a mystery reader, I’m a series lover. When a new book in a favorite series comes out, I can hardly wait to read what’s new among the protagonist’s family and friends and what hot water the protag has gotten into this time. The first series I ever fell in love with long predated my introduction to mysteries. I took Elswyth Thane’s six Williamsburg novels out of the library over and over and over again. To this day, I could probably draw the family tree of the intertwined Day, Sprague, and Campion families from the Revolutionary War to World War II. The publication of the long-awaited seventh book signaled what was probably my first moment of awareness of the New York Times bestseller list. Evidently I was not alone.

When I discovered Amazon, I found the Williamsburg novels in a library edition. I was delighted to meet Thane’s characters again. The only problem was that I remember the books too well. The publisher had bowdlerized a few details for the library audience, and it irritated me like, er, a thorn in a lion’s paw. In This Was Tomorrow, set mostly in London in World War II, the American Stephen Sprague falls in love with his British cousin Evadne, who is innocent and passionate and given to Causes. There’s a scene (I didn't have to look this up--I remember it perfectly) in which Stephen offers Evadne her first drink of champagne, and she defies the repressed Hermione (who has drawn her into the Oxford Group and is jealous and controlling) to drink it. In the original, Evadne snatches the glass and stutters, “Give me that champagne!” The library edition renders it, “Give me that wine!” Lead balloon. I guess the publishers agreed with Thane that champagne represents all that is daring and sinful—too daring and sinful for libraries.

Saturday, May 12, 2007

Hey, It's Different for Me

Reed Farrel Coleman (Guest Blogger)

I envy readers. No, I really do. When I see the sheer joy my wife gets out of reading, I confess to being more than a touch jealous. Between traditional reading and books on tape and CD, she goes through two to three books a week! Not me. For one thing, I may be a quick writer, but I’m a slow reader. Second, reading is no longer just about pleasure for me. For me, reading is part dissection and part analysis. It’s difficult to lose myself in a book the way I once did. An occupational hazard, I suppose.

I remember Orson Welles once being asked, by Merv Griffin of all people, if he enjoyed movies. “No,” he said. “I know too much about the process to be taken in.” It is no coincidence that Welles was an accomplished magician. Magicians don’t say wow, they ask how. The joy of the trick is lost on them. Writers ask how too.

When I wrote Lee Child to compliment him on One Shot, his email reply was very telling and much along the lines of Welles’ view. Although this isn’t quite an exact quote, it’s very close. “I take that as high praise,” he wrote, “from someone who knows how the man behind the curtain works the machinery.” When writers read, they are always looking behind the curtain for the Wizard of Oz.

There’s yet another factor that robs me of some of the joy of reading. As a New York based author and someone who’s held high office in Mystery Writers of America, I’ve had the great good fortune of meeting and developing relationships with a broad range of authors. Some incredibly famous. Some relatively unknown. Many, like me, in that murky mythical land of the midlist. The odd thing about my good fortune is that I often get to know the writer before I have the opportunity to know his or her work. So when I pick a book off my bedside stack, it can be a perilous activity. There can be a personal price to pay if I like an author more than his or her work. I have been lucky in that I have yet to come to blows or lose a friend over this issue, but I’d be lying if I said there haven’t been some pretty awkward moments on panels and at conventions.

It doesn’t end there. These days, I am frequently asked to blurb books—though I’m not quite sure why—judge books for awards, and to act as a first reader for some of my colleagues. Blurbs are a very touchy subject in the business and there’s a broad spectrum of opinion on the issue. In fact, blurbing probably deserves its own dedicated blog. I will say that people have been very generous to me with their praise, so that when I read to blurb, I read with both a critical eye and open heart. However, a judge and or a first reader needs, for obvious reasons, to leave his heart out of the equation. I would be doing a disservice as a judge and first reader to give anything but my most critical assessment. As you might imagine, these sorts of activities don’t exactly add to my reading pleasure.

There is still the rare occasion when I lose myself in a book and enjoy the act of reading the way I did before choosing the life of a writer. In the last two years, it’s happened three times. The books were Die A Little by Megan Abbott, Winter’s Bone by Daniel Woodrell, and Miami Purity by Vicki Hendricks. Although Megan and I have subsequently become good friends, we were only casual acquaintances when I first read the book. I’m also now an occasional first reader for her. I think Vicki and I have met in passing at a Bouchercon and I’ve never met Daniel. But I was so impressed by Miami Purity that I sent an unsolicited blurb to her new publisher and I sent an embarrassingly gushing fan letter—my first real fan letter—to Daniel Woodrell.

So, yeah, reading is different for me and I’m really kind of jealous of the freedom enjoyed by the casual reader or mystery fan. And those rare occasions when I can get in touch with that unbridled joy are marvelous, but they are few and far between. On balance, I wouldn’t give up my writing to regain my innocence as a reader. There are many days, however, when I struggling with a single paragraph or sentence, that it does seem like a deal I might be willing to make.

Reed Farrel Coleman's The James Deans won the Shamus, Barry, and Anthony Awards for Best Paperback Original. His new book, Soul Patch, is in bookstores now.

Thursday, April 5, 2007

Getting Lost in a Good Book

A few weeks back, Sandy Parshall used the expression “getting lost in a good book” in her blog post about the joys of suspenseful reading. It set off a train of association for me about how that happens and how it feels. As a mental health professional, I can tell you that the psychological phenomenon involved is dissociation. Getting lost in a book or movie, along with the long-distance driver’s road trance, is at the mild end of the same spectrum as dissociative identity disorder: the extreme condition that used to be called multiple personality. While it’s certainly not pathological, getting lost in a book produces the same effect of coming to with a jolt from a world that made the one you’re actually in vanish completely. There’s the same sense of having been somewhere else and having no idea how much time has passed.

Sandy also mentioned how sorry she is for people who miss this pleasure because they don’t read. A similar discussion was going on at the same time on DorothyL, triggered by some mystery writers’ experience of strangers—obviously not fans—who email or come up to them to announce that they only read non-fiction or that they only read the Bible. For me, it takes fiction—a story—to sweep me away that completely. My husband is a history buff and inveterate non-fiction reader. He’s always trying to involve me in his reading. He’ll chuckle aloud and say, “Listen to this!” as a preface to telling me some priceless tidbit about Napoleon or Frederick the Great. (When Death Will Get You Sober comes out, you’ll see I borrowed this trait for one of my characters.)

The standard answer to that or any other interruption in our house is, “Shush! I’m reading my bookie.” “Bookie” is our private baby talk for genre fiction, a novel on the light side of what the Brits call “a good read”—a story absorbing enough to sweep the reader away. It goes with teddy bears and cuddling up to read. My husband sometimes complains that it’s not fair to shush him, since I don’t always refrain from talking to him while he’s reading. But the truth is that he’s more willing to be interrupted when he’s reading serious history or something dense and weighty like a book by John McPhee. He’s absorbed, but not to the point of dissociation. I’ve noticed that when he lightens up enough to pick up a mystery, science fiction, or fantasy, he too says, “Shush! I’m reading my bookie.”

What lures me most intensely into an alternate world? While I read more mysteries than anything else, they were not the first books that sprang to mind. Historical fiction with endearing characters and a dollop of romance and fantasy can do it. I remember the pleasure of reading Diana Gabaldon’s Outlander for the first time. It utterly pulled me into the 18th century. Dorothy Dunnett’s Lymond books take me just as thoroughly to the 16th century. Come to think of it, Lois McMaster Bujold’s Miles Vorkosigan series, set in the galactic future and on an old-fashioned planet within it, does the same. The common elements are lovability and a touch of romance, combined with highly intelligent writing, brilliant characterization, and superb storytelling. Of course, there’s plenty of that in mystery too. I don’t want to come back from Judge Deborah Knott’s North Carolina or Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes’s England (and points east and west) either. So shush! I’m reading my bookie.

Saturday, February 17, 2007

Reading as a Writer

At Left Coast Crime in Seattle two weeks ago, a woman asked me what I liked to read. Her question, and three days of hanging out with readers, only some of whom are also writers, prompted a realization. Or maybe it’s a confession:

I am not a normal reader.

And I’m kind of sorry about that.

Writers are readers, too, of course, but some conferences – and LCC Seattle was one of them – are programmed with a focus on the readers who aren’t writers. Writers adore these readers. Readers admire writers, ask about their days, their process, when the next novel or story is being published. Even where they get their ideas, a question that the much-published often scorn but that I’m still new enough to enjoy answering.

Readers who go to cons aren’t just potential buyers. They’re the heart of the writing world, the people we do this for. The people we want to satisfy most, after ourselves. They’re the people we once were.

They can sit for hours in front of the fire with a good book, and sometimes even a bad one, only getting up for more tea or a visit to the bathroom. I miss that. Me, I’m reading with a notebook nearby where I jot down an image that works or doesn’t, note an awkward sentence, question the use of point of view. I read wondering if some detail is going to play out later in the story the way I think it is, or if it’s a red herring. Or worse, a bit of sloppy writing that diverts me for no good reason. I’m reading with one eye on the magician’s hands and the other on the curtain, asking How did she do that?

Readers don’t feel compelled to finish a book just to see if the writer can pull it off.

Readers keep reading a series they enjoy without feeling like they can’t spend the time on a book they’re not likely to learn new tricks from, or that they should be reading the new hot thing.

Readers choose a book because it looks good, not because they want to know why it made the NY Times Bestseller list despite lousy reviews, or why it got great reviews but tanked.

Last weekend, Judy Clemens wrote here about discovering mysteries. And what she described started with her love of the genre, how she couldn’t wait to find out what Lord Peter said to Harriet Vane next, how she scoured bookstores in unfamiliar towns for new discoveries. Only later did she realize she could try writing the kinds of books she loved to read.

I am convinced that when I started writing fiction, my work took the shape of a mystery because that’s what I’d been reading and listening to. I’d been working several days a week in a city 45 miles from home, a city whose library held an excellent audio collection. Many of those tapes – and they were tapes, back then – were mysteries: Sue Grafton, Sara Paretsky, Tony Hillerman, Ellis Peters, Elizabeth Peters. What I loved to read became what I needed to write.

Writers, remember that connection that first brought you to the page. Remember the joy. Your readers want that experience, too; honor their passion. Take time to relive that experience yourself. Pick up a book you last read ten years ago – or one you’ve been saving for a snowy day – and read it again for sheer fun. Leave your review notebook by your desk, and keep your bottom in your reading chair. Stay up too late reading just because it’s fun.

The more you do that, the more that joy will dust your own manuscripts.

In the spirit of remembering the books that brought us here, let me paraphrase Jane Eyre: Reader, I thank you.

Leslie Budewitz is a published short story writer with novels in progress. She provides legal research for writers through Law & Fiction, www.lawandfiction.com.