In my mystery novel which will launch near the end of April, Every Last Secret, Skeet Bannion’s best friend owns a shop called Forgotten Arts, offering knitting, spinning, and weaving supplies. This shop is basically in the book because I love to knit, spin, and weave, and I’ve always had a little daydream of having just such a shop of my own.

In my mystery novel which will launch near the end of April, Every Last Secret, Skeet Bannion’s best friend owns a shop called Forgotten Arts, offering knitting, spinning, and weaving supplies. This shop is basically in the book because I love to knit, spin, and weave, and I’ve always had a little daydream of having just such a shop of my own.It probably all began with my grandmothers. One of them was an excellent needlewoman who taught me to sew doll clothes and doll quilts, using the scraps from her many sewing and quilting projects. This grandmother even made spring corsages for each granddaughter from old nylon stockings, cut up and dyed into violets, iris, lilies, and roses. The other grandmother knit and crocheted afghans, sweaters, even golf-club covers. Neither of them knew how to spin or weave, as far as I know.

Both of my grandmothers were great “makers from scratch,” though, whether with food, such as bread, butter, cheeses, and such, or with household items, such as baskets, candles, lotions, soaps, washcloths, and dish towels. My Cherokee grandmother even made her own medicines with herbs from her garden and weeds growing in the wild. Most of these medicines, foods, and household items were more effective or better-tasting than the mass-produced versions available in stores and pharmacies.

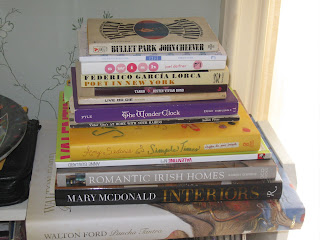

Beginning as a childhood apprentice to these two grand old dames, I set off on a lifelong quest for the forgotten arts. I have a huge library, and one of the categories within it is that of how-to books. I have books on how to design and make furniture from cast-off materials, how to make braided rugs, how to make doll houses and furniture, how to make canned foods and jellies, how to make your own purses and shoes, and books on yogurt making and felt making—and I have made all of these things and more. I seek out books on forgotten arts, such as spinning, weaving, smocking, rug hooking, tatting, and bobbin-lace making. (I’ve done the first three, but haven’t tried the last three yet.) I even have books on how to build your own log cabin or barn from scratch, how to milk a goat, and how to grow and use your own natural-dye garden. If all these dystopian books come true and we have some kind of societal collapse, I’m the neighbor you want to have.

Of course, now that writing has taken over my life, my big floor loom in one end of the living room has become a cat gymnasium, my sewing machine sits permanently covered on a table where manuscripts have replaced fabric pieces, and gorgeous hand-knit projects languish neglected and unfinished in tote bags hanging from the doorknobs of my combination office and studio. I still believe these crafts have great value. I used to make time for them in a busy life, but I’ve lost that knack somewhere and need to recover it for a sense of balance. Meanwhile, I’ll write into my books a character who has that balance and that fiber craft store that I used to dream of owning.

In your own writing, what aspect of your life finds its way as a part of your story? Do you give a character some passion or aspect of your own personality? And when you’re reading, do you like to see these bits of the author’s personality embodied in the work?

|

| Detail of one of Linda's quilts. |

************************

Linda Rodriguez’s novel, Every Last Secret, winner of the St. Martin’s/Malice Domestic Best First Traditional Mystery Competition, will be published by Minotaur Books on April 24. Linda is the author of two award-winning books of poetry and a cookbook, and is the recipient of several writing awards. She swears she’ll shoo the cat off and warp the big loom just as soon as she finishes her book tour and the edits on her second novel in the Skeet Bannion series and the first draft of her third and…

To learn more, visit www.LindaRodriguezWrites.blogspot.com.